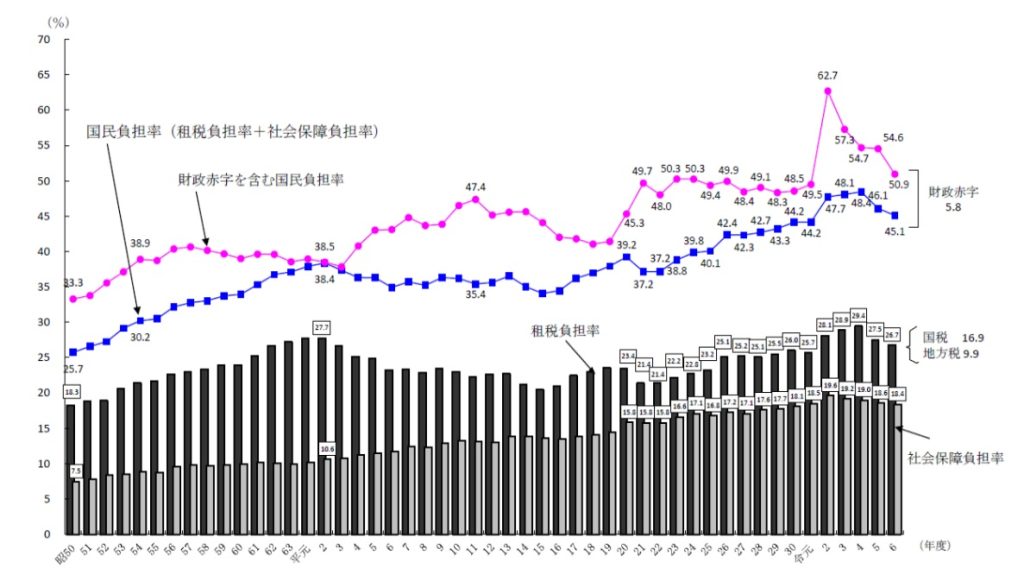

As the Japanese society ages, national pensions, medical expenses and other social expenditures inevitably grow. So does the national contribution to it. The figure shows that the overall trend of the total contribution per national income in on a long term rising trend. Icreasingly, the younger generations are voicing concern that their contribution is way too high, and some even see, or believe to see, a conspiracy by the Ministry of Finance to raise revenue more in order to offeset the budget deficit, and politicians are clandestinely working under this MOF Cult.

It is very unlikely this is true. Indeed, the MOF was investigated by the prosecution in the 1990s for corruption charges and quite a few ranking officials were forced to leave, and their securities section became independent as the Financial Services Agency. The last MOF official who became the prime minister was Miyazawa and his tenure ended in 1993, together with the traditional political dominance of the Liberal Democrats.

In any event, the social expenditures need to be financed, if not by government debts, by taxes or statutory contributions, hopefully not from the working age Japanese. Why not, then, raise the inheritance tax? The taxable assets are not theirs, but their parents’ and the inheritance tax can be viewed as a deferred asset tax triggered only by the assetowner’s death. If the tax is used to finance social expenditures, it constitutes intra generational transfer from those who have to those who don’t.